Spidermonkey Island in the Voyages of Dr. Doolittle is a fantasy island that floats around the South Pacific Ocean, but floating islands actually exist. And they could be a new technology for cleaning up polluted waters and restoring wildlife populations.

Natural floating islands are common in boggy, swampy regions throughout the world. They are referred to as tussocks, floatons, and sudds, and form in a variety of ways. Florida, for example, experienced a high number of floating islands during flood conditions in 2004 after a four-year drought, as reported by the state’s Department of Environmental Protection. They have some unusual biology. Large patches of peat and moss from these islands can become dislodged and float free, blocking drainage pipes or even wiping out boat docks. Small trees such as willows can take hold and act as sails, causing the islands to move about at the whim of the wind.

But in Bruce Kania’s mind they are a solution. Kania invented and patented an artificial floating island he calls BioHaven, and founded the company Floating Island International in Montana.

BioHaven islands come in 45 sq. ft sections made up of multiple layers. The top is textured, slow-to-saturate, marine foam that holds starter plants, followed by several layers of recycled spun plastic mesh. The structure mimics natural floating islands. By planting fauna, such as wetland species, the plants can clean polluted waters. During the 10 years since the development of BioHaven, over 4,000 floating islands have been launched in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and various states throughout the U.S.

This green technology can be used to treat out flowing, or effluent, sewage from wastewater treatment plants, act as wetlands for animals and migratory birds, and treat nutrient-rich runoff from agriculture, according to Floating Islands International. BioHaven Islands can remove nitrogen, phosphorus, ammonia, heavy metals and total suspended solids from polluted water. Aquatic food chains can easily be disrupted if any of the previously mentioned elements are highly concentrated in a body of water, leading to an ecosystem breakdown.

“Adding a small island to a one acre pond would reduce algae blooms and encourage newts, dragonflies, fish and other aquatic species in just one year,” Laddie D. Flock, CEO of Floating Islands West in California, tells SciJourner. “The cost is relatively cheap compared to other tools used to treat polluted waters. A 100 sq. ft. island is perfect for a small pond and will run around $3,000.” As for the cost versus benefits, Flock’s favorite response is, “One island is better than no island.”

The life expectancy of the floating island is about 20 years, but is replaced by natural biomass buildup within a couple of years, says Flock. It continues to stay afloat after the original material is long gone by filling up with naturally-occurring biogas, which forms from both aerobic and anaerobic processes.

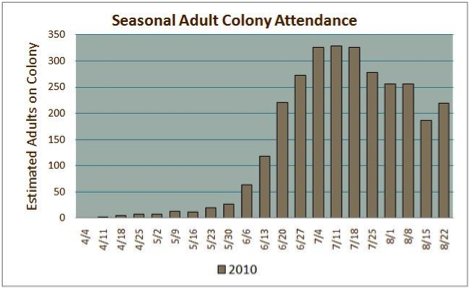

Flock says that BioHaven’s biggest success story is with Sheepy Lake in California and the Caspian Tern Management Project in the Columbia River estuary. The project is a partnership between Oregon State University, Real Time Research, and the US Geologic Survey-Oregon Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Study. The study is looking at whether floating islands are a good tool relocating water fowl nesting sites alleviate feed pressure on limited populations of salmon offspring. The study wraps up this August, but data from June 2010 documented 440 Caspian terns, 1277 Ring-billed gulls, 551 California gulls, and 33 tern nests with eggs on the artificial island structures designed by Kania and his team.

Kania told Wired magazine in April, 2011, that his inspiration for BioHaven came from his childhood. Kania grew up in Wisconsin where natural floating islands are commonplace. Predators, such as foxes, mink and other hungry carnivores, can decimate ground-nesting birds, but are unable to reach floating islands.

Kania’s ultimate goal is to help get water quality back to natural levels so “mother nature” has the chance to restore balance.

“It is not the only answer to water pollution but is a start in the green direction” says Flock.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License

Im glad to learn about the new green technology and ow it is helping the Earth and its wonderful creatures.:smile

Interesting. :smile